Everything Can Change in a Single Moment

We sat on the chair lift looking at the snow-covered mountain below us, our legs swinging, heavy with boots and skis. The icy, hard-packed snow wasn’t the best condition, but the sun was shining and it was warm and we’d left our coats in the lodge when we took a break in the late morning for breakfast burrito.

As the chair rose slowly up the mountain, Carter said “I just love New Mexico.”

”I do too,” I said.

I was holding that moment close to my heart, and I realized: there’s a day coming when I won’t be able to enjoy this anymore.

I was thinking about the cancer that smolders in my bones and the fact that I was five years out from my diagnosis, and that the median survival rate was five years, so I was beating the odds every day.

Instead of saying exactly what was on my mind, I said, “I don’t know what kind of grieving process I would have to go through if I couldn’t ski or ride my motorcycle anymore.” Carter nodded in acknowledgment ,but he’s 21 with his whole life ahead of him, so he really couldn’t understand what I was thinking.

“Let’s come down through the Gamble trees,” I suggested.

“Looks kinda scraped off,” he noted.

Carter took quite a few years off from skiing as a teenager but he’s a natural, and I probably should’ve listened to him. I’d actually felt a bit off all day, like I was barely avoiding the trees and not skiing gracefully--maybe even a little out of control and out of sorts. We had come down a run called Flowers earlier in the day and the snow was pretty good there, but we both like to explore and from the chairlift, Gamble didn’t look that bad. Upper Gamble is a glade that circles around from the top of the upper lift to Lower Gamble at the top of the lower lift. It’s a moderate black diamond all the way down. Nothing I haven’t done maybe a thousand times before.

Carter came to New Mexico by way of Florida. During my cancer treatment in Walla Walla, Washington, it seemed like everything fell apart for everyone. My daughter Katie Jo ended up in San Diego and she loves it there. Carter got in trouble and was struggling through his teen years, but he graduated from high school and got himself a little apartment. While he got his legal troubles sorted out, his mom and my youngest daughter Nanette moved down to Sarasota, Florida, and Katie Christianson and I moved to Santa Fe New Mexico. Carter got his shit together and decided to move in with his mom and little sister in Sarasota while he figured out what to do next. During the summer, we flew him out to visit us and he fell in love with New Mexico. During the next few months, he got three of his friends together and they rented a place in a little town near the Sipapu ski resort, and they all got jobs in the kitchen. Because of my cancer and my compromised immune system and treatment I haven’t really gotten to spend much time with Carter since before he turned 17, so now skiing with him at Sipapu felt a true miracle, and my heart was bursting with joy and pride.

We took the top part of the run without much trouble even though the snow was marginal, and it was hard to get an edge because of the icy conditions. I followed Carter through the trees till we found the lower lift, and we started down lower Gamble. About a quarter of the way down, we crossed over a cat track that had an icy cornice. Carter took the jump over the edge and I followed him a few moments later, skis to snow. It’s the last accurate memory I have. Sometimes I try to conjure a picture of what happened next, but my mind is a blank as I try to see back in time, and I’m grateful I can’t.

I woke up queasy and disoriented with three members of the Ski Patrol hovering over me. To my right, I could see a tall tree and two smaller trees. To my left I could see a stanchion of the chairlift. I wasn’t exactly sure where I was, but I knew I was in trouble by the frantic looks on the faces of the Ski Patrol. My memory is murky at this point still. They splinted my arms and got me into the toboggan for a bumpy ride down the hill. At the patrol shack, they set me up in a wheelchair, and I could see my broken arms for the first time. A trickle of blood ran down the bridge of my nose as one of my rescuers flashed a light in my eyes.

Carter had been waiting at the base after trying to contact me on the radio. When Ski Patrol found me, they took my radio out of my vest pocket so I could talk. I don’t remember it, but apparently, I told him I’d been in a “bit of a crash” and was “just a little shaken up.” When he saw the sled coming in, I was zipped all the way into the bag, so the first thing he saw as they unbundled me was my bloody face, and I was incoherent. He told us later that was the scariest moment of his life, seeing his dad’s bloody face and watching him slip in and out of consciousness. Still, he kept his wits about him and called Katie who had stayed home to work.

I could hear him relaying information to Katie. “Dad’s been in a crash. He hit a tree. It’s not life-threatening, but he’s probably got one or two broken arms. They’re taking him to Holy Cross in Taos.”

“Is she coming?” I asked.

“She’ll be here in about an hour,” he said.

Carter got the Jeep keys out of my jacket and followed the ambulance down to Taos. Katie met us in the emergency room. The x-rays looked bad. In fact, the x-ray technician said, “You really did a number on your wrists.” The ER doc administered local anesthesia to my wrists and set them as best he could.

The accident was around 11 in the morning, and we got back to our house in Santa Fe at about 11 that night. The pain meds were wearing off and I was starting to get a sense of just how badly I was injured. The wrist ends of the radial bones were shattered, and the ulnar bones broken off at the end. It would take surgery with titanium plates to pu it all back together. To make matters worse, I had just started a new job, had very little sick leave, and it looked like I’d be off work for quite a while. In fact, Katie and I had just come from a very rough summer where my post-cancer treatment symptoms had forced me to take time off work, so I had resigned my position at the college and Fortune had not yet favored us, so we were once again out of money. This job I had just started was a godsend, and now it was all in jeopardy.

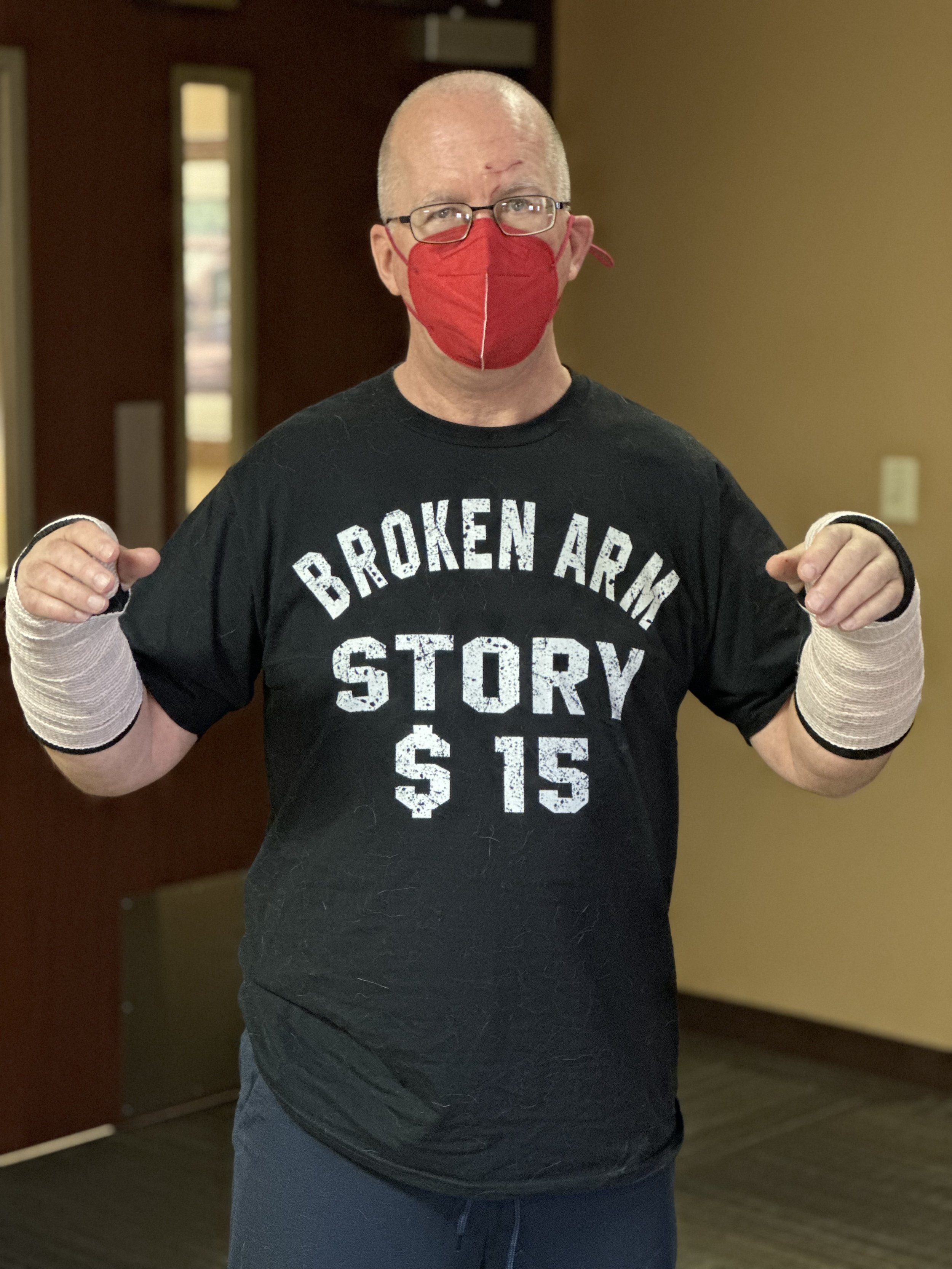

It’s been three weeks since the accident. I am starting to regain some mobility in my arms and hands. My employer has graciously allowed me to work from home, and even though I’ve used up the tiny bit of sick leave I had accrued, I am able to take leave without pay right now. Surgery went well. The surgeon here is nationally recognized and he only had to use one titanium plate for each wrist. Two days ago, they removed my stitches and replaced the heavier casts with lightweight splints. I am writing this using voice to text. I’ll leave it to Katie to edit. It’s awkward, and I don’t speak the way I like to write. I’ve spent a lot of time with fingers on keyboard and it almost feels more natural to me than spoken word. I dressed myself this morning and put my contacts in. I opened a jar of jam at breakfast this morning. I welcome the little miracles at this point.

I’m focusing now on healing. Still, right now, even simple movements are painful. I can’t make a fist. With my elbows at my sides, I can’t put my palms up to the sky, but I am starting to be able to face them to the floor. I can pick up a coffee cup and I’ve been able to take up journaling every morning again. I asked the surgeon if he thought I’d be able to play guitar again. He was skeptical, but I know I need to have goals. When Katie told him that I might like to ski again at least one more time this year before the season is over, I’m pretty sure the expression I saw was a scowl.

After my stem cell transplant in late September 2018, my medical team told me it would be at least 100 days before I could start getting back to normal life and that it would be six months to two years before I could do normal things again. Katie’s son Nick loaned me his Wii and I purchased a little ski game for the balance board. In November, I could barely stand on the board. I would walk to the mailbox and back daily. As the month progressed, I walked farther and farther until I was walking downtown, and I kept playing the ski game, looking forward to when I could hit the slopes again. On December 17, my surgeon declared my cancer in remission, and I asked him when I could ski again. With a few promises of good behavior and some convincing, he agreed that I was ready to hit the slopes. We skied on December 23 with Katie’s son Kurt and his girlfriend Emmy. It was a brilliant snowy day and we stood knee-deep in powder and cried. I know first-hand the power of having a goal like being able to ride my motorcycle in the spring or ski one more time before the season closes in early April, and to hear Katie sing as I play her favorite songs on one of my many guitars.

I’m not ready to give up yet, and I’m not ready to have anyone tell me that I can’t do something.

I like to think I didn’t manifest this injury when I spoke aloud how I might grieve if I couldn’t ski or ride anymore. It’s more likely it was just random coincidence. I’ve been skiing for 50 years and the worst injury I’ve ever had was a sprained thumb. Also, I’ve been trying to manifest a writing career for almost that long and haven’t yet succeeded, although I feel like I might be close. Just two days ago, I found out that my horror/sci-fi screenplay, The Spread, is one of three finalists in the George R. R. Martin script contest put on by the New Mexico Film Foundation. The Director of the foundation said that he had also read the screenplay and thought it was “fantastic.”

Katie and I have had some massive bad luck over the past five years since cancer diagnosis, and I think it’s about time we had some massive good luck to make up for it. I will concentrate on my physical therapy. I will give my job 100%. When I am healed, I will ski again and I will ride my motorcycle and I will play guitar. Also, I will keep writing and keep hoping and focusing on the good things in my life like my kids, my wife, and this glorious place we call home.

During cancer treatment, Stephen, our favorite care coordinator, told us, “Those who do best with this treatment are the ones who can find the gift in the situation.” I try to take that thought into all our daily situations. I haven’t found a gift yet in having two broken arms, but I’ll keep trying. In the meantime, I will focus on what Katie always says as we face each day: “forward facing, solutions oriented.” Or even more simply, one day at a time.